Lead and copper are naturally occurring metals that have often been used in indoor plumbing. Pipes and plumbing may contain lead, copper, or their alloys, such as brass; some solder used at copper pipe joints may also contain lead. Water, particularly corrosive water, can dissolve small amounts of these metals into drinking water. The potential for leaching increases the longer the water is in contact with plumbing components.

Exposure to lead and copper may cause health problems ranging from stomach distress to brain damage. Both lead and copper are harmful when ingested, but lead is more toxic because it can accumulate in the body. Lead damages the brain, nervous system, kidneys, reproductive system, and red blood cells. It is more toxic to children than to adults, and it can harm their mental and physical development. Copper is much less toxic than lead; however, elevated levels of copper for 14 days or more can cause permanent kidney and liver damage in infants under the age of one year and it can cause nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea in people of all ages.

On June 7, 1991, EPA published a regulation to control lead and copper in drinking water. This regulation is known as the Lead and Copper Rule. The treatment technique for the rule requires systems to monitor drinking water at customer taps. Because lead and copper in drinking water is mainly due to the corrosion of service lines and household plumbing, tap water samples are collected at kitchen or bathroom taps of residences and other buildings.

If lead concentrations exceed an action level of 15 parts per billion (ppb) or copper concentrations exceed an action level of 1.3 parts per million (ppm) in more than 10 percent of customer taps sampled, the system must undertake additional actions such as corrosion control treatment (CCR).

Lead

Lead is a toxic metal that was used for many years in products found in and around homes. Although lead is found in nature, most exposure comes from human activities or use. Lead-based paint and lead-contaminated dust are the primary sources of exposure for children. Lead is sometimes used in plumbing materials or in water-service lines used to bring water from the main line to homes, schools, or other buildings.

Health Effects of Lead

Lead is a significant health concern, particularly for children, whose developing bodies are more susceptible to its harmful effects. Adverse health impacts from lead include damage to the brain and kidneys, reduced IQ and attention span, learning disabilities, poor classroom performance, hyperactivity, behavioral problems, and impaired growth. The primary source of lead exposure for most children is lead-based paint in older homes. Lead in drinking water can add to that exposure.

Lead in Drinking Water

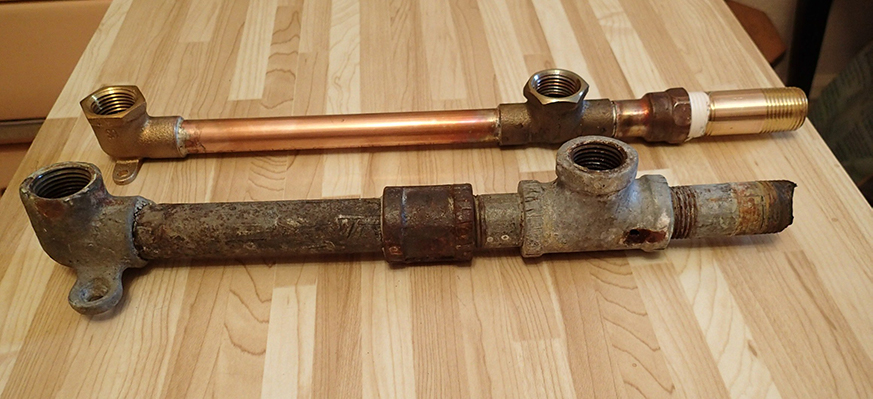

In Utah, most drinking water sources from reservoirs and groundwater are lead-free. When lead is present in water, it is typically due to water flowing through lead pipes or plumbing in buildings. Service lines — the pipes that connect homes, schools, or other buildings to the water main — can also have lead in them. There may also be lead pipes, pipes connected with lead solder, or brass faucets or fittings containing lead inside homes or schools. Lead levels are highest when the water has been sitting in lead pipes for several hours. Additionally, using hot water can draw lead out of pipes, solder, or fixtures and release it into the water.

Action Level for Lead in Drinking Water

EPA is required by law to determine the level of contaminants in drinking water at which no adverse health effects are likely to occur. These health-based goals are called maximum contaminant level goals (MCLGs). EPA set the MCLG for lead in drinking water at zero because the best available science has not been able to determine a safe level for lead in drinking water. However, the agency has set an action level of 15 parts per billion (ppb) that triggers additional actions by public water systems if over 10 percent of the faucets sampled exceed this level.

Steps to Reduce Lead in Drinking Water

Public water systems employ a number of measures to ensure water is safe to drink. The Safe Drinking Water Act’s (SDWA’s) Lead and Copper Rule requires public water systems to control the corrosivity of their water. Systems must collect samples at customer taps in homes that are more likely to have plumbing materials containing lead. If the lead concentrations exceed the 15 ppb action level in more than 10 percent of the taps sampled, the water system must take additional actions to control corrosion. SDWA also requires public water systems to prepare and distribute an annual water quality report called the Consumer Confidence Report (CCR) to its customers. The CCR contains information about any contaminants found in the water, including lead. Most lead problems in homes, however, do not originate with the finished drinking water provided by the water supplier, but from lead pipes, solder, and fixtures within the house.

Lead Sampling

Lead samples are taken at the highest risk sample sites (based on year of construction) and during the warmest months of the year when the highest lead levels are expected to occur. Samples are collected from a kitchen or bathroom tap after the water has been standing in the pipes for at least twelve hours, with a “first-draw” sample collected first thing in the morning before any water has been used. This ensures that the samples contain water that is most likely to accumulate metals, like lead, from corrosion.

Home Testing for Lead in Drinking Water

Residents with concerns about lead levels in the drinking water at their home can have their water tested for lead. Homeowners may want to test if their home has lead pipes or if they see signs of corrosion. Water systems sometimes offer free testing for customers with concerns about the quality of the drinking water in their house. Residents can call their water system using the phone number on their most recent water bill to see if testing services are available. The water supplier may also provide useful information, including whether the service connector used in the home or area is made of lead. Testing is especially important in apartment buildings where flushing might not work. If residential water comes from a household well, homeowners can check with their health department or local water systems that use ground water for information on contaminants of concern in their area.

Residents who wish to test their water themselves should use a state-certified lab for sample analysis. The Division of Drinking Water has compiled a list for homeowners of instructions on how to collect samples, and when to return samples to the lab.

Steps to Reduce Lead in Residential Drinking Water

- Flush pipes before drinking. The more time water has been sitting in a home’s pipes, the more lead it may contain. The most important time to flush is after long periods of non-use, such as first thing in the morning, after work, or upon returning from vacation.

- Use only water from the cold-water tap for drinking, cooking, and especially for making baby formula. Hot water is likely to contain higher levels of lead.

- Utilize household water-use activities — showering, washing clothes, flushing the toilet, or running the dishwasher — for flushing pipes and allowing water from the distribution system to enter household pipes.

- Do not boil water to remove lead. Boiling water will not reduce lead in drinking water.

- Check with the public water supplier in areas served by older water systems to see if they have lead pipes or service lines and if they have been replaced partially or in whole. In many lead service-line replacements, the replacement will only have been to the meter, and there may be lead service-lines after the meter and lead pipes within the building. To determine if the property has a lead service line or lead pipes, hire a licensed plumber to inspect the service line and replace all lead pipes.

- Purchase replacement plumbing products that have been tested and certified to “lead-free” standards.

Copper

Copper is a naturally occurring metal found in rock, soil, water, and sediment. Pure copper is red-orange but becomes blue-green when exposed to air and water. Copper is used in many different products, including wire, plumbing pipes, and sheet metal. Pennies made before 1982 are made of copper, while those made after 1982 are only coated with copper. Copper is also combined with other metals to make brass and bronze pipes and faucets.

Health Effects of Copper

A small amount of copper is essential for good health. The Food and Drug Administration recommends a dietary allowance of 2 milligrams (mg) of copper a day. But exposure to high doses of copper can cause health problems. Short-term exposure to high levels of copper can cause gastrointestinal distress, and long-term exposure and severe cases of copper poisoning can cause anemia and disrupt liver and kidney functions. While some of the copper people consume enters the bloodstream rapidly, the body generally excretes excess copper after several days. Individuals with Wilson’s or Menke’s disease, genetic disorders resulting in abnormal copper absorption and metabolism, are at higher risk from copper exposure than the general public.

Copper in Drinking Water

Low levels of copper can be found naturally in all water sources. However, drinking water that has been left standing in household copper pipes for long periods of time is usually the main cause of higher levels of copper. The major source of copper in drinking water is corrosion of household plumbing, faucets, and water fixtures. Water absorbs copper as it leaches from plumbing materials such as pipes, fittings, and brass faucets. The amount of copper in drinking water depends on the types and amounts of minerals in the water, how long water stays in the pipes, the water temperature, and acidity.

Action Level for Copper in Drinking Water

EPA is required by law to determine the level of contaminants in drinking water at which no adverse health effects are likely to occur. These health-based goals are called maximum contaminant level goals (MCLGs). EPA set the MCLG for copper in drinking water at 1.3 parts per million (ppm) in drinking water, which is identical to the action level that triggers additional actions by public water systems if over 10 percent of the faucets sampled exceed this level.

Steps to Reduce Copper in Drinking Water

The Safe Drinking Water Act’s (SDWA’s) Lead and Copper Rule requires public water systems to control the corrosivity of their water. Systems must collect samples at customer taps in homes that are more likely to have plumbing materials containing copper. If the copper concentrations exceed the EPA copper action level of 1.3 parts per million (ppm) in more than 10 percent of the taps sampled, the water system must take additional actions to control corrosion. SDWA also requires public water systems to prepare and distribute an annual water quality report called the Consumer Confidence Report (CCR) to its customers. The CCR contains information about any contaminants found in the water, including copper.

Copper Sampling

Copper samples are generally taken during the warmest months of the year when the highest copper levels are expected to occur. Water should stand in the pipes for at least 12 hours, with a “first-draw” sample collected first thing in the morning before any water has been used. This ensures that the samples contain water that is most likely to accumulate metals, like copper, from corrosion.

Home Testing for Copper in Drinking Water

Residents with concerns about copper levels in the drinking water at their home can have their water tested. Blue-green stains on plumbing fixtures, for example, may indicate elevated levels of copper in the water, and a high level of copper usually leaves a metallic or unpleasant bitter taste in the drinking water. Water systems sometimes offer free testing for customers with concerns about the quality of the drinking water in their house. Residents can call their water system using the phone number on their most recent water bill to see if testing services are available. If residential water comes from a household well, homeowners can check with their health department or local water systems that use ground water for information on contaminants of concern in their area.

Residents who wish to test their water themselves should use a state-certified lab for sample analysis. The Division of Drinking Water has compiled a list for homeowners of instructions on how to collect samples, and when to return samples to the lab.

Steps to Reduce Copper in Residential Drinking Water

- Flush pipes before drinking. The more time water has been sitting in a home’s pipes, the more copper it may contain. The most important time to flush is after long periods of non-use, such as first thing in the morning, after work, or upon returning from vacation.

- Use only water from the cold-water tap for drinking, cooking, and especially for making baby formula. Hot water is likely to contain higher levels of copper.

- Utilize household water-use activities — showering, washing clothes, flushing the toilet, or running the dishwasher—for flushing pipes and allowing water from the distribution system to enter household pipes.

- Do not boil water to remove copper. Boiling water will not reduce copper in drinking water.

- Be mindful of copper exposure in newer homes with copper pipes, as they may be more likely to have a problem. Over time, a coating forms on the inside of the pipes and can insulate the water from the copper in the pipes. In newer homes, this coating has not yet had a chance to develop.